By John Bocskay

The North Korean tourist industry, such as it is, got some bad press this year when two American tourists, Jeffrey Fowle and Matthew Miller, were jailed, Fowle for leaving a Bible in a sailor’s club toilet and Miller for as-yet-unspecified crimes against the reclusive state. They both join Kenneth Bae, a Korean American missionary who last year was sentenced to a 15-year all-expense-paid jaunt to a North Korea labor camp for Bible-related assaults on the North Korean regime. The takeaway from last year’s news for would-be tourists was to either obey North Korea’s draconian laws, stay away from North Korea entirely, or be Dennis Rodman, who was the only visitor who appears to have had a rip-roaring good time.

One may sympathize then with Koryo Tours, a small British travel agency that specializes in tours to North Korea. What do you do when your job is to lure visitors to one of the world’s least enticing places?

You design a video game.

Working with a North Korea-based company called Nosotek, Koryo Tours commissioned a browser game called Pyongyang Racer, the first-ever video game developed in North Korea and released for foreign consumption. Designed by Kim Chaek University of Technology students, released on December 18th, 2012, and hosted by the Koryo Tours website, Pyongyang Racer was described as “a bit of retro fun” that not only gives the player “the chance to drive around Pyongyang” but to do it “all by yourself”.

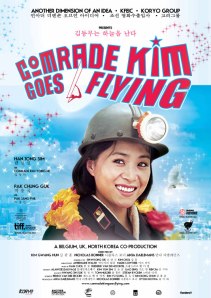

Much has been written about North Korea, and some films and videos have afforded an occasional state-sanctioned glimpse into the entertainment they produce for domestic consumption – think the Mass Games featured in A State of Mind and kindergartners playing guitar, but films produced by North Koreans have gained scant international exposure. In the early 2000’s, I jumped at the chance to see the North Korean monster film Pulgasari when it opened in Busan, though it was justly panned south of the DMZ and few South Koreans I have ever mentioned it to have even heard of it. In 2012, the film Comrade Kim Goes Flying (which Koryo Tours also co-produced) played at the Toronto Film festival in 2012 and even won over some critics, who called it “fun” while noting its “unabashed kitsch.” While it didn’t set the cinematic world abuzz, it was nonetheless a distinct improvement over previous offerings, like the 2008 documentary The Respected Comrade Supreme Commander Is Our Destiny, and represented another baby step for North Korean culture onto the world stage.

Much has been written about North Korea, and some films and videos have afforded an occasional state-sanctioned glimpse into the entertainment they produce for domestic consumption – think the Mass Games featured in A State of Mind and kindergartners playing guitar, but films produced by North Koreans have gained scant international exposure. In the early 2000’s, I jumped at the chance to see the North Korean monster film Pulgasari when it opened in Busan, though it was justly panned south of the DMZ and few South Koreans I have ever mentioned it to have even heard of it. In 2012, the film Comrade Kim Goes Flying (which Koryo Tours also co-produced) played at the Toronto Film festival in 2012 and even won over some critics, who called it “fun” while noting its “unabashed kitsch.” While it didn’t set the cinematic world abuzz, it was nonetheless a distinct improvement over previous offerings, like the 2008 documentary The Respected Comrade Supreme Commander Is Our Destiny, and represented another baby step for North Korean culture onto the world stage.

When I heard about Pyongyang Racer, I knew that my own destiny was to give it a spin. Sure, I assumed that “retro fun” was probably just a way of saying “shoddy crap,” but I share the curiosity many people feel whenever the smallest bit of cultural information trickles out from the most isolated country in the world. Combine that with my interest in video games and it was a no-brainer.

I clicked the Pyongyang Racer link and was disappointed, though not surprised, when the game failed to load, though I later found out that the Koryo Tours website had been hacked within a couple days of the game’s debut. After moving to a new host, they eventually got the game running, and I finally had my chance to visit this Potemkinized, pixilated Pyongyang.

The “About” link on the game site itself explains that Pyongyang Racer “is not intended to be a high-end techological [sic] wonder hit game of the 21st century,” and my first play confirmed that it lives down to its billing. Technologically, the game is a glitch-ridden throwback to the 32-bit era of the early 90’s, though you’re free to think of it as “retro fun” if you prefer.The controls are clunky and unresponsive, the buildings along the road are drab and repetitive, and it’s not even a “race” but an uneventful drive in a Pyonghwa Motors sedan around the mostly deserted streets of Pyongyang, set to an unrelenting soundtrack of bouncy North Korean music oddly reminiscent of the faux North Korean music in Team America: World Police.

However, despite (or because of) its lack of drama or technical brilliance, Pyongyang Racer is loaded with delightful ironies and inadvertent social realism. Unlike American driving games, where the object is usually to compete with other drivers and flout the speed limit without being caught, the two main challenges in  Pyongyang Racer are to scrupulously obey the law and not run out of gas, which would seem to mirror the most pressing concerns of actual Pyongyang drivers. One of the city’s iconic female traffic cops randomly appears and warns you to “drive straight” and to avoid hitting three cars or you will be “stopped for bad driving,” and coyly tells you not to stare at her because she’s “on duty.”

Pyongyang Racer are to scrupulously obey the law and not run out of gas, which would seem to mirror the most pressing concerns of actual Pyongyang drivers. One of the city’s iconic female traffic cops randomly appears and warns you to “drive straight” and to avoid hitting three cars or you will be “stopped for bad driving,” and coyly tells you not to stare at her because she’s “on duty.”

As you drive around, your eyes are more likely to be drawn to your fuel gauge, which depletes rapidly (a full tank lasts less than 2 minutes). You replenish it by running over fuel barrels, which lie scattered along the road, sometimes in the oncoming lane. Lest that sound risky, fear not: there’s very little traffic, and the few cars that do appear have no drivers and don’t move at all, perhaps having been abandoned after running out of fuel.

Though it sounds like a fairly simple task, the first time I played I ran out of gas and the game ended. The second time, I was curious to see what would happen if I hit three cars, but there is so little traffic that I ran out of fuel while looking for cars to hit. It wasn’t until my fourth game that I succeeded in keeping the car moving long enough to ram three other cars. Would I be sent to the gulag for working to undermine the safety of the state, I wondered? Nope. After the hitting the third car, the game abruptly ended. Please forgive the “spoiler”, but it was so lame I didn’t think you’d mind.

The only other point of the game is to collect the little icons that appear in the road next to famous landmarks around the city, which are instantly recognizable if only because they are the only buildings rendered in any detail whatsoever. Running over the icons opens a little blurb about that location. For example, the Arch of Triumph icon proudly states, “Without the traffic jams of Paris.”

Also unlike Paris, there is not a single human being to be seen anywhere on the map, except the cop who constantly watches you and appears out of nowhere. The game makers seem to assume that thething to do in Pyongyang is to be whisked around gawking at monuments with as little human contact as possible, which again jibes with every anecdotal description of Pyongyang tourism that I’ve ever heard. You also have to remain on the predetermined course. Nobody will shoot you, as happened in 2008 to an unfortunate South Korean tourist who wandered into an unauthorized area at North Korea’s Mt. Kumgang resort, but any attempt to drive off the road or take an unsanctioned turn results in a short screen blackout, after which you reappear pointed in the mandated direction as if nothing had happened.

Despite its failings, the game is actually pretty hard to finish. In ten or so plays, I’ve yet to make a full circuit. The main page has a “Top Ten Champions list” though it doesn’t update automatically; if you get a high score, you are instructed to take a screenshot to prove it, and e-mail it to Koryo Tours, along with your time, the number of fuel barrels and tourist sites collected, and the number of cars you hit. The current high score is held by the improbably named Shinmai McBurrobit, who finished the track in 7 minutes, 17 seconds, while collecting all fuel drums and tourist sites and not hitting a single car – in other words, a perfect game. Move over, Billy Mitchell. There’s a new kid in town.

Pyongyang Racer isn’t going to rock your world, but you’re desperate for a unique peek into the Hermit Kingdom, go on and check it out.

Editor’s note: A shorter, less interesting, and more poorly-written version of this piece appeared in March 2013 on Outside Looking In.