By Iwazaru

With the Chinese New Year commencing on January 31, and the Year of the diligent, disciplined and cooperative Wood Horse rising with the new moon, for many in the East it’s a felicitous time to ask what the future holds, be it favorable or frightening. In Korea, some people turn to the blind seers of the Mia-ri district in northern Seoul. This is where I met Diviner Baek Il-hong one frigid January afternoon not long before the spirits of the new year would be unleashed to shape the months ahead. Looking back, I wonder what else she knew.

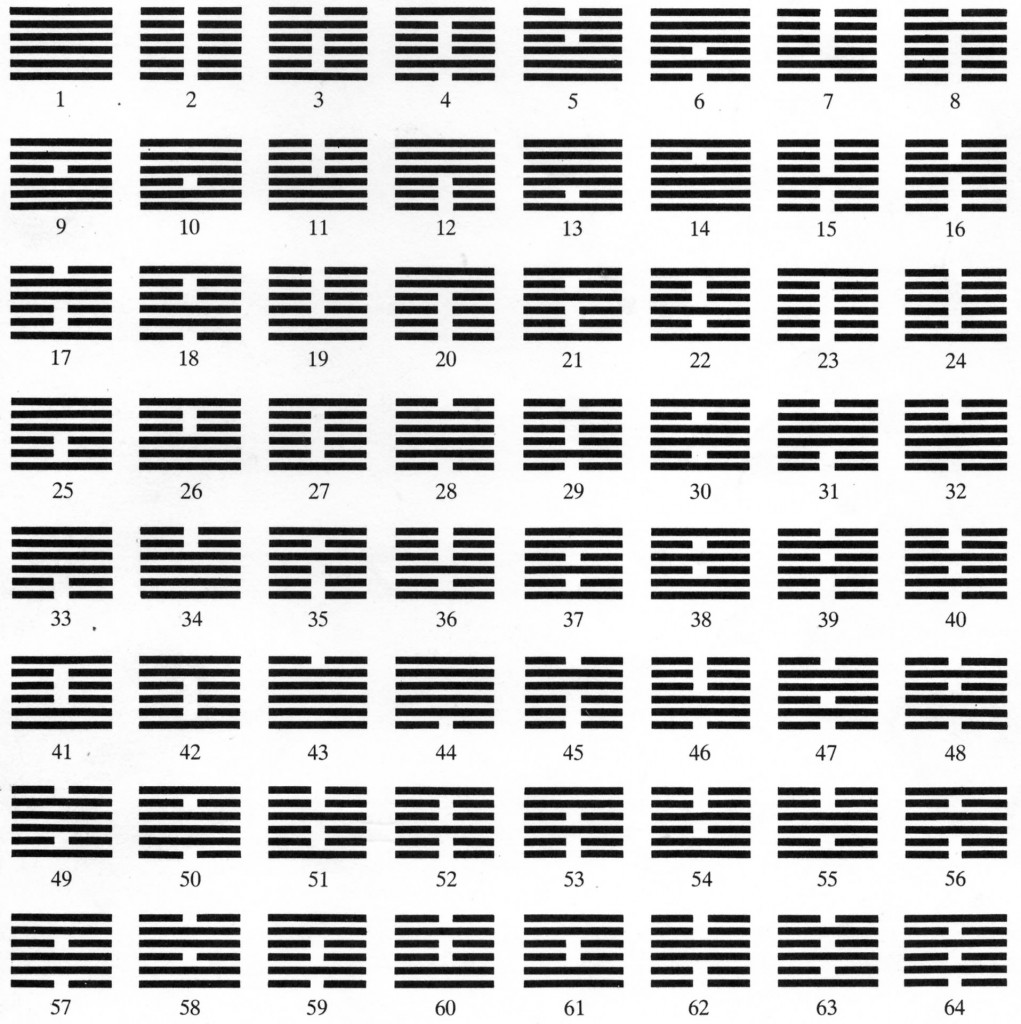

Authentic diviners— aka fortune tellers— in Korea, many who’ve gone through years of education, rely on a combination of Chinese astrology and one Korean book written by a scholar during the Joseon dynasty in the 16th century. The Chinese text originates from an ancient book of philosophy dating back more than 2,000 years called “I Ching” or “The Book of Changes”—scholars say it was first a divination manual used by wizards in the Zhou dynasty (1046–256  BC), and only later considered a philosophical text. It contains 64 symbolic hexagrams that diviners interpret. The Korean book, “Tojeong bigyeol” or “Secrets of Tojeong,” was written by Joseon scholar Lee Ji-ham, also known as Tojeong, who created his own matrix to foretell the future. Diviners consult sections of both texts to read one’s saju, or four pillars, a fortune based on the year, month, day and time of birth—there’s no point in visiting without all this information.

BC), and only later considered a philosophical text. It contains 64 symbolic hexagrams that diviners interpret. The Korean book, “Tojeong bigyeol” or “Secrets of Tojeong,” was written by Joseon scholar Lee Ji-ham, also known as Tojeong, who created his own matrix to foretell the future. Diviners consult sections of both texts to read one’s saju, or four pillars, a fortune based on the year, month, day and time of birth—there’s no point in visiting without all this information.

Despite the science and numerical reliance of traditional divination, there is an obvious mystery that enshrouds it. This is not the magical mystic with the crystal ball conjuring up things, the smoke and mirrors in proper place; this is a professional diviner gathering your specific birth information, matching it with numbers from ancient texts, then shaking a small, steel case shaped like an egg (called a santong), which holds tiny, rectangular bamboo fortune slips, each one carrying a specific force to shape the final divination, depending on whether or not it emerges from a narrow slot at the top. The outcome is a series of extrapolations pulled from the past, stretched into the present and projected through the fog of the future, illuminating various elements that lie ahead.

To find Diviner Baek, I rode the Seoul subway north to Mia-ri, and, upon exiting the underground station, I was met by the concrete catchall that is Seoul: apartments, banks, churches, coffee shops, convenience stores, clinics and various academies. No mist. No street-side stalls with diviners hunched over inside foretelling the future. Just another anonymous subway exit. A few minutes later as I walked, I spotted the first 역학원 sign on my left down a side street, which indicated a diviner’s place of business, or a yokhagwon. As I continued ahead, the main road on the right began to ascend above the sidewalk creating a rising concrete wall opposite a one-story stretch of brick, concrete, glass and signage on my left. This was the place.

Baek Il-hong went blind at the age of three after a life-threatening case of the measles. Now in her 60s, Baek has a right eye that’s milky and made me think of a cloudy day in November. It provides only enough vision for her to identify movement and shapes. Her left eye has no vision and remains closed. Yet it is clear that she must have been pretty as a younger woman, something that she was not shy about admitting. Her hair is still a thick raven black and her skin, with few wrinkles, glows like a summer sea shell. Asked about her own fortune she offered, “It said I would be a diviner or the owner of a brothel.” History  and the blind seers themselves say that divining was one of the few jobs the blind were able to pursue in the past. Masseuse and prostitute were two others. Baek explained that she began her studies at the age of eight, saying that she knew that, “studying hard was my only chance.” Although Baek offered few specifics about her grade school work and secondary studies, she said she’d spent years learning how to interpret the I Ching and Tojeong bigyeol; both texts are in Braille. She emphasized that she uses some elements of I Ching and the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac, but mostly relied on Tojeong. At the age of 20, she did her first divination in Mia-ri and has been reading fortunes ever since. “Back then it was much busier because there were fewer of us,” she said. “In the last 20 years many more diviners have moved here.” It is rather clear that Baek has done well given the size of her space on the main drag and the upkeep on her traditional Korean hanok home that sits behind the frontal façade of business signs and glass.

and the blind seers themselves say that divining was one of the few jobs the blind were able to pursue in the past. Masseuse and prostitute were two others. Baek explained that she began her studies at the age of eight, saying that she knew that, “studying hard was my only chance.” Although Baek offered few specifics about her grade school work and secondary studies, she said she’d spent years learning how to interpret the I Ching and Tojeong bigyeol; both texts are in Braille. She emphasized that she uses some elements of I Ching and the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac, but mostly relied on Tojeong. At the age of 20, she did her first divination in Mia-ri and has been reading fortunes ever since. “Back then it was much busier because there were fewer of us,” she said. “In the last 20 years many more diviners have moved here.” It is rather clear that Baek has done well given the size of her space on the main drag and the upkeep on her traditional Korean hanok home that sits behind the frontal façade of business signs and glass.

What is her secret? “I have built a reputation over the years with my divinations,” she said. “People know if you can do your job…then they come back.” Baek listed her regular visitors as mothers searching for auspicious omens about their kids’ upcoming exams (exams that usually determine one’s future in Korea), single women wondering about their luck in love, sick people hoping to ward off evil spirits, and politicians desperate for a read on their political future. “Politicians come often and are the most reactive,” she said regarding the actions of politicians whom reject her readings. “If they don’t like what they hear, they will get up and walk right out in the middle.” However, she said, they often return a year or two later: “They come back because they see that I was right and they want to get another reading.” In fact, I found, the election season is one of the busiest times for diviners. The other precedes the yearly college entrance exam, the suneung, administered over one full day each November.

Now, there are doubters who snicker at the idea of divination, dismissing it as mumbo jumbo or akin to snake oil. I had my own skepticism so, before visiting Baek, I sought more tangible evidence and began asking Korean acquaintances if they could recall an occurrence when the diviners had told their family something that had implications. Most people didn’t want to say much about it if they knew anything (a superstitious sentiment surrounded the issue) or just said that that was something only grandparents would know about. Then, one day, a younger Korean friend whose grandparents have visited diviners for many years shared a personal story involving her own parents. It began with her grandmother visiting a diviner to find out how compatible her future parents were. Apparently, the diviner forewarned that the two should not get married given what the four pillars forecast. There were ominous omens. Nevertheless, the couple went ahead with the wedding (something that the grandparents still have not let go). Following the marriage, one grandmother again paid her visit to the local Buddhist temple to have a monk read the future of the marriage. (Many monks have similar training to what Diviner Baek and other diviners receive; they are also able to read the four pillars.) This time the reading advised the couple not to have a son in the year of the pig under the Chinese zodiac. If they did, the father would die soon thereafter. The birth of a son followed in 1995, the year of the pig. Within months, the father, in his early 30s, was diagnosed with cancer. He battled the disease for six years and then passed away at the age of 38. His daughter says that her grandmother still visits the diviners every year and often has talismans to ward off evil spirits.

Diviner Baek read my four pillars with the same seriousness that a doctor some years ago advised that I would need emergency surgery after I had been ambulanced in from a nearly fatal car crash. Saju provides general information about one’s life and specific details about what the months ahead may hold. Sitting cross-legged on the floor at a low wooden table with a bamboo fortune slip between her small fingers and two texts in front of her, Baek said I have no luck from my parents or siblings—I am on my own. I should not inherit anything or it will all be lost. After confirming that I was not married, Baek said that  was a good thing because it would have been ruinous. “You will find someone next year,” she prophesied. “She should not be overly intelligent because conflict could arise.” Then her face tightened and she asserted that an evil spirit had come to me when I was 26 and remained; this I was at first perplexed by. “You need a talisman,” she advised. “You must wear it around your neck for seven days then burn it.” She was not happy when I asked to move on, but she did. A promotion from January to March. Meeting significant people from April to June. Don’t travel to foreign lands in the summer. I will live to be 89. From 55 to 60 I will do much philanthropic work. “Have you considered the talisman?” she asked. Could we continue, I replied. “You should open a hotel or an academic institution,” she added. “The talisman?” Her insistence made me return to age 26—and the Korean way of determining age. A baby’s age is one year old at birth and then he or she turns two with the new year. After thinking, it approximately worked out that I was 26 “Korean age” when I started having intestinal problems related to that surgery my doctor notified me about some years before; acute problems that incapacitated me for several days at a time and led to two hospitalizations. Evil spirit is almost an understatement. But I could be stretching for a connection—I could be.

was a good thing because it would have been ruinous. “You will find someone next year,” she prophesied. “She should not be overly intelligent because conflict could arise.” Then her face tightened and she asserted that an evil spirit had come to me when I was 26 and remained; this I was at first perplexed by. “You need a talisman,” she advised. “You must wear it around your neck for seven days then burn it.” She was not happy when I asked to move on, but she did. A promotion from January to March. Meeting significant people from April to June. Don’t travel to foreign lands in the summer. I will live to be 89. From 55 to 60 I will do much philanthropic work. “Have you considered the talisman?” she asked. Could we continue, I replied. “You should open a hotel or an academic institution,” she added. “The talisman?” Her insistence made me return to age 26—and the Korean way of determining age. A baby’s age is one year old at birth and then he or she turns two with the new year. After thinking, it approximately worked out that I was 26 “Korean age” when I started having intestinal problems related to that surgery my doctor notified me about some years before; acute problems that incapacitated me for several days at a time and led to two hospitalizations. Evil spirit is almost an understatement. But I could be stretching for a connection—I could be.

I never bought the talisman; they range in price from hundreds of dollars to tens of thousands or more (depending on the malevolence of the spirit), and I wasn’t a believer. I did get a promotion in February, but I didn’t find a nubile woman all year. I met a venerable Korean monk on a mountain that May with whom I still correspond. In July, I traveled to and from America, unscathed. I haven’t opened a hotel or academic institution, yet. And, well, I’m still alive. So, sometimes, when uncertainty or misfortune visits me, I think of Diviner Baek, I see her cloud-filled eye behind which the known and unknown swirl, I wonder if she would’ve seen, if she could’ve warned me, if the talisman would’ve protected me, if the future really is knowable, and if knowing would really matter.